|

Arizona's desert is home to some of the oldest living animals on Earth: dinosaur shrimp, or triops, meaning three eyes. Triops are crustaceans belonging to the order Notostraca, which dates back over 300 million years ago. They have survived mass extinctions, ice ages, and continental drifts. I first encountered these little creatures a couple of years ago during the monsoon season. We had gotten unusually plentiful rainfall that year, and one day, after a hard rain, I took a walk on our land, which is in the high deserts of Arizona. I was just looking around as one does when one lives out in the middle of nowhere in Arizona after a rain. I found the ordinarily bone-dry wash was suddenly full of chocolate water. I was looking specifically for tadpoles because the desert toads will emerge during the summer rains and breed. I did find some tadpoles, but I also spied something else swimming in the muddy water: dinosaur shrimp. Being the nature lover I am, these creatures that I had never seen before excited me. They were orange in color and looked like tiny horseshoe crabs. I knew nothing about them, so I did some research. I thought I would share some of what I learned. Triops have three eyes: one on top of their head and two on the sides. They have a segmented body with a carapace that covers their head and thorax. They have a long tail with two forked appendages called furcae. They can grow up to 10 cm long and come in various colors, such as green, brown, red, or blue. The ones I saw were reddish orange. They live in ephemeral pools of water that form after rainstorms or snowmelt, or in our case, the chocolate waters that flow from powerful monsoons. The waters that birth these tiny dinosaur shrimps can range from a few centimeters to several meters deep and last from a few days to several months. The shrimp have a remarkable adaptation to survive in these temporary habitats: they can produce eggs that can withstand desiccation, freezing, and high temperatures for decades until they encounter water again. When the eggs hatch, the shrimp go through several molts and reach maturity in about two weeks. They can reproduce both sexually and asexually, depending on the environmental conditions. The lifespan of dinosaur shrimp is up to 90 days. Their actual life cycle depends on the water quality they are in and the availability and quality of food they have access to. Dinosaur shrimps are omnivorous and eat zooplankton, insect larvae, algae, and bacteria. They also scavenge on dead organic matter and will even cannibalize their own kind. They will, in fact, eat almost any organic material they can fit into their tiny mouths. Dinosaur shrimp are considered living fossils because they have changed very little over time. They are essential to the desert ecosystem because they help recycle nutrients and organic matter in the water. They also provide food for birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Some Native American tribes consider triops sacred and use them for ceremonial purposes. For example, it is believed that dinosaur shrimp are a symbol of life and renewal and have a connection to their ancient ancestors. Dinosaur shrimp may have been a source of food and medicine. For example, the Navajo boil dinosaur shrimp and drink the broth to treat stomach ailments. The Hopi use dinosaur shrimp in rituals to bless their crops and livestock. Dinosaur shrimps are not endangered in Arizona but are threatened by habitat loss, pollution, and climate change. Their eggs can survive for years in dry desert conditions but need water to hatch and grow. If the pools dry up too quickly or become contaminated, the dinosaur shrimp population will decline. Climate change may also affect rainfall patterns and the temperature of their habitat, making it harder for them to survive. Dinosaur shrimps are not harmful to humans. And believe it or not, they have been sold as pets for years! You can buy triops kits on Amazon to raise your own. The kits have everything you need to grow, house, and nurture your very own prehistoric shrimp ancestor. And if you ever visit Arizona at just the right time, you might be lucky enough to spot some of these ancient wonders of nature in the wild. *Watch the video Hundreds of Dinosaur Shrimp Emerge After Arizona Monsoon that discuss dinosaur shrimp (Triops longicaudatus) that have been found in the ball court pond at Wupatki National Monument in Arizona.

0 Comments

by Rodney Taylor

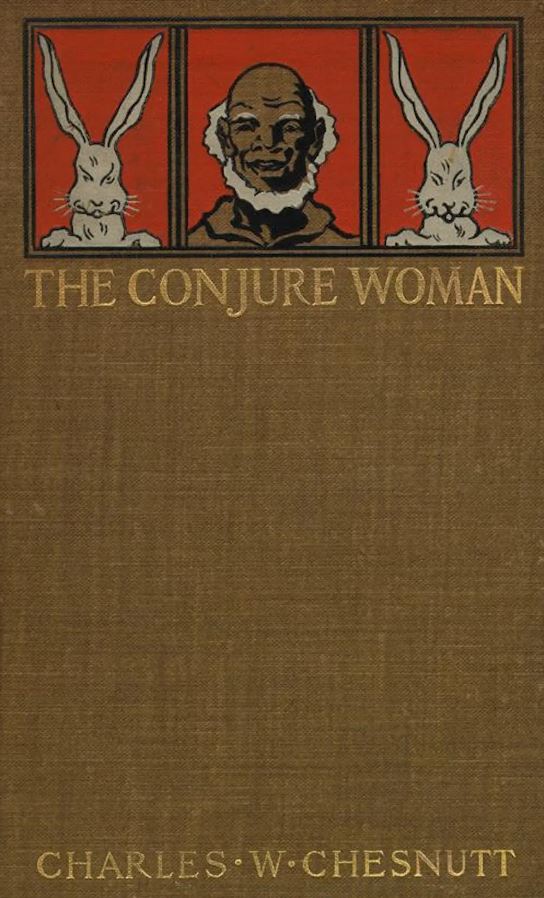

Postdoctoral Fellow in African American Studies, University of South Carolina Any writer has to struggle with the dilemma of staying true to their vision or giving editors and readers what they want. A number of factors might influence the latter: the market, trends and sensibilities. But in the decades after the Civil War, Black writers looking to faithfully depict the horrors of slavery had to contend with readers whose worldviews were colored by racism, as well as an entire swath of the country eager to paper over the past. Charles Chesnutt was one of those writers. Forced to work with skeptical editors and within the confines of popular forms, Chesnutt nonetheless worked to shine a light on the legacy of slavery. His 1899 collection of stories, “The Conjure Woman,” took place on a Southern plantation and sold well. At first glance, the stories seemed to mimic other books set in the South written in a style called “local color,” which focuses on regional characters, dialects and customs. But Chesnutt had actually written a subversive counternarrative, using humor to poke holes in the nostalgic myths of the South and expose the contradictions of a racist society. Rewriting the pastAfter the Civil War, there was a concerted effort to portray the South as a pastoral place possessed with a culture of honor. Slavery, meanwhile, had been a nurturing, even benevolent, institution. These beliefs bled into the era’s fiction, with white authors such as Thomas Nelson Page and Joel Chandler Harris writing stories that sentimentalized and softened the complex histories of the past. Many of these stories feature a formerly enslaved older male who’s given the affectionate moniker “Uncle.” These characters tended to describe the Civil War as an affront on the Southern way of life, while presenting the South and its landed gentry as heroic. In “A Story of the War,” for example, Harris introduces the character Uncle Remus, who recounts the time his master went away to fight the Civil War. Overcome with concern for the man who enslaved him, Uncle Remus follows him and witnesses a Northern soldier preparing to shoot him. In a moment of panic, Remus shoots the Northerner, wounding him. “A Story of the War,” like most Southern local color tales, appealed to readers invested in the Lost Cause of the Old South, a revisionist ideology that depicts the creation of the Confederate States and cause of the Civil War as just and heroic. Historian Fred Bailey notes that stories like Page’s and Harris’ were “hailed by the South’s upper-classes,” while associations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy routinely read from these works at their meetings. Chesnutt’s Revisionist Humor At first glance, it would seem Chesnutt, who was mixed-race and could have easily passed for white, was merely working within the dominant literary form of his time and fashioning stories geared to a white audience. Like his white contemporaries, Chesnutt, in “The Conjure Woman,” includes a character who’s an “uncle” living on the abandoned plantation where he once toiled. But Chesnutt, as literary historian Dickson Bruce points out in his 2005 essay “Confronting the Crisis: African American Narratives,” used the setting of the plantation to present a more authentic representation of slavery. Uncle Julius, who appears in each of the collection’s stories, isn’t nostalgic for some bygone era. Instead, he reflects on his own life and seeks to show the humanity of the enslaved. He uses his ability as a raconteur to cleverly swindle a white carpetbagger who bought the plantation Julius lived on during his bondage and after the Civil War. The stories are descriptive, corrective – and, most importantly, funny. While Chesnutt’s tales explicitly engage with the hard history of slavery, each of the stories ends on a lighter note, with Uncle Julius often getting what he wants. Throughout the collection, he parodies the conventions of Southern fiction – whether refuting racist tropes or showing the cruelty of the ruling class – subtly poking fun at a culture enveloped by the fog of nostalgia. Bound by Form At the same time, Chesnutt felt as if he couldn’t simply write broadsides against myths like the Lost Cause. In order to be published, Black writers needed to appeal to the sensibilities of white readers and the demands of editors. For example, Uncle Julius spoke in a Black dialect that sounded similar to those of the uncles authored by white writers. This didn’t come easily for Chesnutt. In one letter to his editor, Chesnutt described writing in this dialect as a “despairing task.” Nonetheless, he avoided completely pandering to mainstream expectations of how Black characters should be portrayed. He rejected the emergent historiography of Reconstruction that refused to recognize the agency of African Americans, and despite working within the form, Chesnutt didn’t present Julius as a buffoon who was happy to serve the whites in his midst. Even though his stories didn’t overtly denounce racism, Chesnutt hoped they might still chip away at prejudice: But the subtle almost indefinable feeling of repulsion toward the negro, which is common to most Americans – and easily enough accounted for, cannot be stormed and taken by assault; the garrison will not capitulate: so their position must be mined, and we will find ourselves in their midst before they think it. Humor Opens Doors Chesnutt is far from the only Black artist asked to make compromises. Poet Langston Hughes had a falling out with his patron, Charlotte OsgoodMason, who viewed African Americans as a link to the species’ primitive past and wanted his work to be devoid of political progressivism. As Hughes wrote in his 1940 autobiography, “The Big Sea,” “I was only an American Negro – who had loved the surface of Africa and the rhythms of Africa – but I was not Africa. I was Chicago and Kansas City and Broadway and Harlem. And I was not what she wanted me to be.” In Chesnutt, I also see ties to contemporary Black comedians who center their humor around race. During the third season of “Chappelle’s Show,” Dave Chappelle famously suffered from an existential crisis because the comedian wasn’t sure how people were responding to his humor. In a 2006 interview with Oprah Winfrey, he explained how, when filming a sketch in blackface, “someone on the set, that was white, laughed in such a way – I know the difference of people laughing with me and laughing at me. And it was the first time I’d ever gotten a laugh that I was uncomfortable with.” Shortly after, Chappelle quit the show. While Chesnutt was certainly not the first African American artist to use humor to depict the horrors of slavery, he was one of the first to reach the American mainstream. The humor disarms readers, helping them cross a psychological threshold and enter a space where a more nuanced conversation about the history of the country can take place. * This article was first published on the Conversation. Keywords: Black writers, Charles Chestnutt, White supremacy, humor, literature, Langston Hughes, Black History month, lost cause, American South

From Kali to Mary to Neopagan Goddesses, Religions Revere Motherhood in Sometimes Unexpected Ways6/11/2023 by Alyssa Beall Teaching Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Humanities, and Philosophy, West Virginia University As we approach Mother’s Day, many groups will hold special events or services to celebrate the holiday. In the United States, Mother’s Day was originally founded in 1908 at Andrews Methodist Episcopal Church in West Virginia and became a nationally recognized holiday in 1914. The mid-May date spread around the world, though many countries still maintain their own dates and traditions. Religions around the world use these days to honor the importance of many kinds of nurturing, from traditional celebrations to events that honor modern parenting, infertility struggles or the pain of losing a child. Motherhood and nurturing are not celebrated only on particular days, however. Many religions include goddess-centered traditions that embrace many forms of the divine feminine as central to their belief systems. As a religious studies professor who travels with students around the world to explore different cultures and practices, I have often noticed the interest students have in the variety of goddess traditions we encounter. Asian traditions Guan Yin, who goes by many variations of her name, is revered as the goddess of compassion and mercy in several different Eastern traditions. Beginning – interestingly enough – as a male bodhisattva called Avalokiteshvara, the goddess figure was adapted in many different cultures around the world. Called Kannon in Japan and Quan Am in Vietnam, she is frequently a focal point of temple worship and is also considered the guardian of sailors and a goddess of fertility. One of the most well-known goddesses in Hinduism, meanwhile, is perhaps the least understood from an outside perspective. Kali is often seen as a terrifying figure, depicted using multiple weapons and dressed in clothing of severed heads and arms. Yet Kali is also an important mother figure who channels her ferocity into the care and defense of all creation. As a manifestation of the primal force of Shakti, Kali is essentially all aspects of motherhood wrapped up into one, often simultaneously caring, loving and fierce. The triple goddess In Neopaganism, an umbrella term for a diverse group of new religious movements most popular in the United States, Australia and Europe, goddess figures also often play a primary role. Neopaganism’s various branches include Wicca and Hellenic reconstructionism, a religion that focuses on the gods and goddesses of Ancient Greece. Of primary importance for many Neopagans is the triple goddess, a figure who encompasses the three aspects of maiden, mother and crone. Sometimes these goddess figures are based on specific ancient deities, such as Persephone, Demeter, and Hekate, and sometimes they are worshipped more generally as representations of various phases of life. More recently, many of these traditions are intentionally expanding to reject ideas of gender essentialism and embrace a range of identities. For some Neopagans, exploring what femininity and masculinity signify in today’s society is an important extension of religious belief and a way to include people who have felt rejected from other religious communities. Beyond the goddess Many other religions revere mother figures, even if they are not worshipped or considered goddesses. Khadija, the wife of the Prophet Muhammad and the first convert to Islam, is given the title “the Mother of Believers,” signifying her importance for the development of the religion. Devotion to Mary, mother of Jesus, has been common throughout the history of Christianity and remains popular today. In Judaism, the idea of “Shekinah” has been influential in some feminist thought. Rather than representing a single woman or female figure, Shekinah is seen as the feminine aspect of the divine, a manifestation of God’s wisdom on Earth. Nurturing and compassion are key concepts in a variety of religions, whether they are represented as specific goddess figures, archetypes of the feminine or new religious developments that embrace shifting ideas about gender. * This article first appeared on the Conversation. One of the most common and versatile ingredients in magick is bird bones. Bird bones have been used for centuries by various cultures and traditions for different purposes, such as divination, protection, healing, and enchantment. In this blog post, I will explore some of the ways that bird bones can be used in magick and how to obtain them ethically and respectfully. Divination Bird bones can be used as a tool for divination, or the practice of seeking knowledge of the future or the unknown by supernatural means. There are different methods of using bird bones for divination, such as casting them on a cloth or a board with symbols and interpreting their patterns and positions or holding them in your hands and feeling their vibrations and messages. Some practitioners use specific types of bird bones for specific types of questions, such as owl bones for wisdom, raven bones for secrets, or dove bones for love. Chicken bones in particular are popular among New Orleans Voudou practitioners as tools of divination. They are also considered good luck. Protection Bird bones can be used for protection, or the practice of shielding oneself or others from harm or negative influences. There are different ways of using bird bones for protection, such as wearing them as amulets or charms, burying them around your property or home, or placing them in a jar or a mojo bag with other protective herbs and stones. Some practitioners use specific types of bird bones for specific types of protection, such as Chicken bones to guard good luck, eagle bones to grow courage, hawk bones for vision to see that which needs to be protected, or swan bones for grace. Healing Bird bones can be used as tools for restoring health and well-being to oneself or others. There are different ways of using bird bones for healing, such as making them into teas or tinctures, grinding them into powders or pastes, or burning them as incense or offerings. Some practitioners use specific types of bird bones for specific types of healing, such as crane bones for longevity, hummingbird bones for joy, or peacock bones for beauty. Enchantment Bird bones can also be used as a tool for enchantment, or the practice of influencing or changing the qualities or behaviors of oneself or others by magical means. There are different ways of using bird bones for enchantment, such as carving them into runes or symbols, stringing them into necklaces or bracelets, or embedding them into candles or dolls. Some practitioners use specific types of bird bones for specific types of enchantment, such as crow bones for transformation, sparrow bones for luck, or phoenix bones for rebirth. How to obtain bird bones ethically and respectfully Bird bones are sacred and powerful items that should not be taken lightly or disrespectfully. If you want to use bird bones in your magick, you should always obtain them ethically and respectfully. This means that you should never kill a bird or harm a living bird for its bones. You should only use bird bones that come from natural sources, such as roadkill, found remains, or ethical hunting. You should always ask permission from the spirit of the bird before taking its bones and thank it afterwards. You should also cleanse and consecrate the bird bones before using them in your magic and dispose of them properly when you are done. Birds have long been a source of inspiration for humans, not only for their beauty and grace, but also for their ability to produce a variety of sounds and melodies. Some of the earliest musical instruments ever made were flutes carved from bird bones, dating back to the Paleolithic era. One of the most remarkable examples of these ancient flutes was recently discovered in northern Israel, at a site that was once a wetland teeming with migratory birds. The flutes were made from the wing bones of coots and teals, small waterfowl that were hunted by the Natufian people, who lived in the Levant region about 12,000 years ago. The Natufians were hunter-gatherers who practiced some of the earliest forms of agriculture and animal domestication. They also had a rich cultural life, as evidenced by their elaborate burials, artistic expressions, and musical instruments. The flutes have holes bored into them, which allow them to produce different pitches when blown into. Researchers from the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem tested replicas of the flutes and found that they could mimic the sounds of birds of prey, such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and the Common Kestrel. This could have been a clever hunting strategy, as the flutes could have been used to scare away the waterfowl, making them easier to catch as they took flight. Another possibility is that the flutes were played for musical purposes, perhaps as part of rituals or ceremonies. The Natufians may have used them to imitate the sounds of nature, or to create their own melodies and songs. One of the flutes was found intact, which is very rare for such an ancient artifact. It is also one of the oldest musical instruments in the world, and a testament to the creativity and ingenuity of our prehistoric ancestors.

A recent archaeological discovery was made by workers digging a road in Poland. A grave containing 450 headless 'vampire' skeletons was found with the skulls placed between their legs and coins in their mouths. This was believed to stop the dead from returning from the grave and to ensure their passage to the afterlife. This is a rare and intriguing example of how people in the past dealt with their fears of the undead and tried to prevent them from rising again.

The grave site was located in Luzino, a village in northeast Poland, next to an 18th century church. The road workers who stumbled upon it were shocked to see hundreds of human bones, some of which had been decapitated or placed in unusual positions. The archaeologists who examined the site confirmed that these were signs of anti-vampire rituals that were common in the 19th century in this region. According to Maciej Stromski, who led the excavation, some of the skeletons had bricks next to their head, arms and legs, which were supposed to immobilize them. One skeleton belonged to a woman who had been beheaded and had a child's skull on her chest. Stromski explained that these practices were motivated by superstition and fear of vampires, which were thought to be responsible for causing diseases and deaths among the living. If a family member died shortly after another's funeral, it was suspected that the first deceased was a vampire who had drained their life force. To prevent further harm, the grave was dug up and the corpse was mutilated or reburied in a different way. The belief in vampires was widespread in Europe for centuries and influenced many folk tales and legends. However, it was not until the late 19th century that vampires became popularized in literature and media, thanks to works such as Bram Stoker's Dracula and Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla. These stories portrayed vampires as aristocratic, seductive and powerful beings, rather than as decaying corpses. The discovery of the grave site in Luzino is a valuable source of information for historians and anthropologists who study the culture and beliefs of people in the past. It also shows us how fear can shape our behavior and imagination, and how we try to cope with the unknown and the mysterious. Source Workers horrified as 450 headless ‘vampire' skeletons found while digging up road (msn.com)

Top three things NOT to ask St Expedite for...or me, for that matter (please, really, just don't). WARNING: The following may be found offensive to some folks living in an alternate reality. However, it is based on true requests and reports. Here goes..and hold on to your hats cuz...well...

For more tips, go here to purchase the book The Conjurer's Guide to St. Expedite. |

Denise AlvaradoAuthor and Voodoo Muser, setting lights, working mojo, throwing wanga, and working wonders in liminal spaces and dusty crossroads. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

Follow Us on Twitter

© The Voodoo Muse, All rights reserved worldwide.

Web design by Voodoolicious Designs.

Proudly powered by Papa Legba.

Web design by Voodoolicious Designs.

Proudly powered by Papa Legba.